William Starbuck, professor emeritus at New York University and Courtesy Professor in Residence at Lundquist College of Business at the University of Oregon, presented his work on organizational unlearning.

William Starbuck, professor emeritus at New York University and Courtesy Professor in Residence at Lundquist College of Business at the University of Oregon, presented his work on organizational unlearning.

Starbuck began with a historical overview. Prior to the 1950s, nobody thought of the idea that organizations could learn. As scholars began to study organizational learning, they (perhaps naively) assumed that it was a good thing; that learning meant the firm would do better in the future. Study after study showed that it was instead a mixed bag; learning both helps and hurts. Then in the 1970s and 1980s, scholars began to study collective learning, looking across ecosystems of organizations. The hypothesis was that the organizations that learned would survive and those that did not would fail. But again, scholars found a mixed bag: learning seemed to result in random change.

So why does that happen? If you don’t know what to learn, you will learn the wrong things. But to know what to learn, you need to know the future. And you don’t! So we can’t assure that what we learn is useful. New learning and strategies are equally likely to cause harm.

Starbuck described his early work with NASA. He studying disasters and asked, how are disasters possible with such smart and dedicated people? He found that working teams repeatedly made the same mistakes, in large part because they were not good at figuring out what they did wrong and how they can do it differently.

He and his colleagues began to study organizations in trouble and crisis. Why do organizations get in trouble and what do they do about it? Learning and unlearning were at the heart of that story.

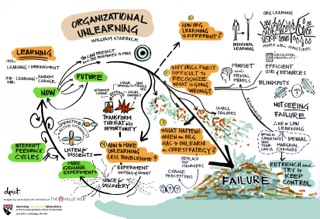

Four topics for today

- How organizational learning is different

- Why organizations find it difficult to recognize what is going wrong

- What happens when organizations have to unlearn their core strategies

- How to make unlearning less troublesome

How organizational learning is different

Individuals, Starbuck noted, can learn without unlearning. Individuals write on top of what they know. Organizations can’t do that because they commit to what they have learned in a formal, structural way. They try to routinize behavior and replicate them and built them into artifacts. They hire a certain type of people and not others. They try to make efficient use of resources. They also must rationally justify every decision and every use of resources, which squashes imagination. All of these things freeze organizational knowledge in place. This makes unlearning more of a salient issue for organizations than it is for individuals.

Why organizations find it difficult to recognize what is going wrong

Because organizations include formal structures, routines, artifacts, and collective action, they move slowly. When faced with smooth, continuous social and technological change, organizations can respond in incremental ways and generally cope well. But social and technological change are generally discontinuous, with slow gradual change plus large shake-ups. Organizations have a harder time dealing with the shake-ups.

First, organizations have to realize that something is going wrong and what to do about it. Poorly performing organizations don’t recognize that they are poorly performing. So they are immune to outside signals. They socialize people into the old way of doing things, and everything becomes further entrenched.

Starbuck offered the example of Facit, a Swedish manufacturer of mechanical calculators that went bankrupt with the advent of digital calculators. They struggled to make the shift to digital, for a number of reasons.

- For decades they had hired the best mechanical engineers, who knew little about electronics – limited range of mindsets.

- Sold off their profitable division to support the “core” business (which was failing) – myopic focus on “what we do best.”

- Interviewed existing (rather than departing) customers only – Locked in by efficient use of resources.

- Political process within the organization – redefining success and failure.

Next, Starbuck discussed his investigation of failure at Eurocom. They matched small failures with similar large failures. In the large failures Starbuck and Baumard revealed:

- Managers said all 7 large failures had had idiosyncratic and exogenous causes.

- They blamed consultants, national governments, or economic fluctuations.

- When failures were bigger, managers saw more idiosyncratic and exogenous causes.

- The costs of large failures were spread over time and hidden by other events.

- People who had headed the large failures moved to other jobs before the failures became apparent. No one was blamed or held responsible, even though some people had participated in multiple failures.

In the small failures, Starbuck and Baumard revealed that managers said that 3 of the 7 small failures also had idiosyncratic and exogenous causes. 4 of the 7 failures were attributed to deviating from Eurocom’s traditional policies about product technology.

Starbuck and Baumard thus concluded: the reinforcement of tradition was the only learning from the 14 failures.

What happens when organizations have to unlearn their core strategies

Starbuck noted he was painting a fairly bleak picture of learning from failure; that is, it doesn’t really happen. Instead, when organizations have to unlearn their core strategies, they often resort to non-effective behaviors.

- First, managers deny that change is necessary.

o They manipulate accounting statements.

o They promise that improvements will happen soon.

- Next, managers make marginal changes that preserve core strategies.

o Often, organizations replace their CEOs but no one else.

o Top managers promise radical changes that will make things better.

- Employees become demoralized.

o Outstanding personnel depart.

o Top managers liquidate profitable activities.

o Everyone comes to distrust the top managers.

- Top managers turn to consultants, but choose consultants who appear to make sense to the current top managers.

o “Consultants are ploys in internal struggles.”

Starbuck studied companies in serious trouble, where half ended up surviving and half did not. In the surviving organizations, all the top management was replaced all at once. Starbuck argues that this is an important and useful strategy. When just one person is new—even if they are the CEO—they quickly become socialized into the dominant mindset. Replacing the entire management team allows new mindsets to grow roots.

How to make unlearning less troublesome

Experiment instead of commit

Starbuck was quick to note that “fake” experiments don’t help, but sincere, well-designed experiments might prove very useful.

Good experiments feature:

- Weakened commitment to success – allows for more creativity and flexibility

- More monitoring of results – allows for enhanced learning and the ability to make rapid changes

- Expectations of correction and refinement – team members are not expected to “get it right the first time;” failure is expected and even welcomed.

However, those kinds of experiments are not common. More typically, participants blame failure on deviation from tradition. They don’t collect enough data. The feedback they receive is too slow in coming, and their commitment to success is too strong. Their evaluation and perception of the project becomes biased towards success, particularly when success linked to career success.

Listen to dissent

Many managers are poor listeners. Starbuck noted that in every case they studied, top managers had some warnings. But executives often ignore them. They dismiss dissenters: “those people don’t really understand the problem.” They steer the conversation away from warnings. They focus on short term at the expense of the long term.

Top managers are also quite isolated. People communicate up, but don’t report problems, and managers often surround themselves with toadies or yes-men.

But dissent is always present – if you have not heard of trouble, you are not hearing the truth! Practicing active listening can help managers get the early warning signs they need.

Transform threats into opportunities

Threats can be transformed into opportunities by following a handful of tactics.

Learn or unlearn. Ask yourself, what is going on that had been unnoticed or misunderstood? Are there better ways we can do things? Were we missing anything? Is this threat a social construction and can we learn new ways to talk about things?

Stage administrative dramas. Encourage staff members to take on the perspectives of others, to get a new view of the problem.

Introduce unrelated change that can be construed as related. Sometimes crisis opens a door to launch overdue changes.