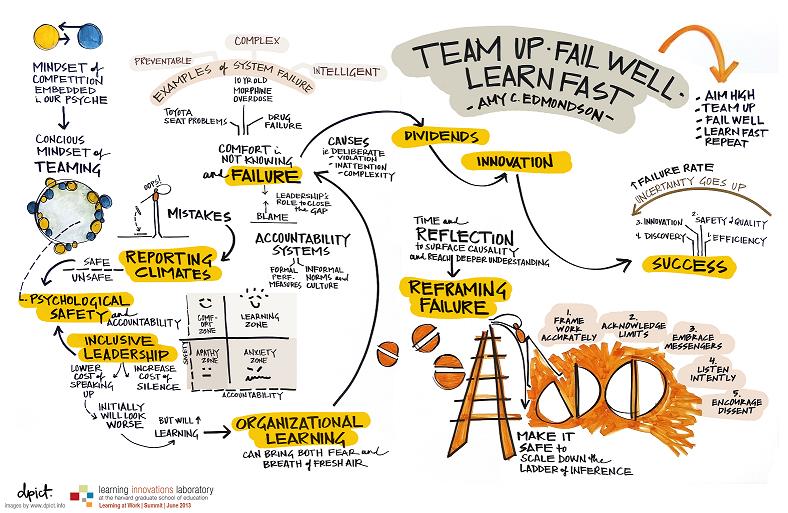

Amy Edmondson, Novartis Professor of Leadership and Management at Harvard Business School, opened by reminding us that a competitive mindset is deeply embedded in our psyche. This mindset is counterproductive because today’s work is profoundly interdependent. We cannot do it alone; we can only do it by teaming up.

Dr. Edmondson then presented medical error rate data from patient care units. Paradoxically, the units with the lowest reported errors were not necessarily the safest, but did have the most hostile reporting climates. Staff members in those patient care units were afraid to report errors because they were shamed and punished for doing so. None of us wants to look ignorant, incompetent, intrusive, or negative, so in a hostile reporting culture, we can try to hide fallibility. Unless leaders create psychological safety–a belief that one will not be punished or humiliated for speaking up with ideas, questions, concerns, or mistakes—fear of blame gets in the way of teaming and learning.

Dr. Edmondson stated that inclusive leadership fosters psychological safety. Leaders who are accessible, proactively invite input, and acknowledge their own fallibility lower the psychological costs of speaking up and raise the costs of being silent.

Dr. Edmondson noted that when creating a culture of psychological safety, leaders need to prepare for the “Worse Before Better Problem.” For example, at Children’s Hospital of Minnesota, Julie Morath created a policy of “blame-free reporting” of medical errors. The number of sy stem-wide patient safety reports first rose steeply, then dropped precipitously as the staff learned to work together to prevent the errors that they were finally acknowledging were taking place.

stem-wide patient safety reports first rose steeply, then dropped precipitously as the staff learned to work together to prevent the errors that they were finally acknowledging were taking place.

Her research has found that leaders often wonder: am I sacrificing accountability if I promote psychological safety? In fact, as this matrix shows, psychological safety and accountability are not mutually exclusive.

Dr. Edmondson highlighted two different types of accountability systems: formal performance management and informal norms and culture. There’s an argument to be made for abolishing the traditional performance review and focusing on leveraging informal norms and culture to build people’s desire to belong and make a difference.

Organizational learning depends on leadership. Several years ago, Dr. Edmondson conducted a case study on minimally invasive cardiac surgery implementation. Sixteen cardiac surgery programs all set out to implement a new technology for minimally invasive cardiac surgery. The challenge was that surgeons now needed the other people in the operating room to really speak up about what they saw. In the past, nurses and anesthesiologists had been trained not to speak unless spoken to. For some, this change was too much. Others were incredibly energized. The research showed that he difference depended on surgeon leadership and the culture of psychological safety that they did or did not foster.

“Anything worth doing is worth doing badly.” This quotation from CK Chesteton reminds us that if something is worth doing, it’s going to require learning. In organizations that innovate, people must be comfortable learning, not knowing, and reporting mistakes. Success is actually not always better than failure.

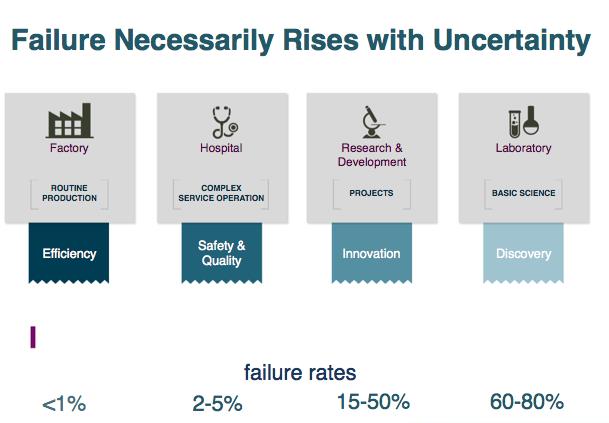

What does succ ess mean? It depends on the level of uncertainty in the setting. In a routine setting like a factory, success is efficient production. In a complex service operation, like a hospital, success is safety and quality. In research and development, success means innovation. In a laboratory, success is discovery, whether or not it is immediately useful. The meaning of failure has to change and expectations for failure have to rise depending on the uncertainty of the setting. In a factory, failure rates should be less than 1%. In a laboratory setting, however, 60-80% of experiments are expected to fail.

ess mean? It depends on the level of uncertainty in the setting. In a routine setting like a factory, success is efficient production. In a complex service operation, like a hospital, success is safety and quality. In research and development, success means innovation. In a laboratory, success is discovery, whether or not it is immediately useful. The meaning of failure has to change and expectations for failure have to rise depending on the uncertainty of the setting. In a factory, failure rates should be less than 1%. In a laboratory setting, however, 60-80% of experiments are expected to fail.

Potential causes of failure include experimentation, uncertainty, complexity, incompetence, inattention, and deliberate violation. Some of these are indeed blameworthy acts, but in many organizations, any failure is treated as blameworthy. There are at least three types of failures: 1) Preventable, 2) Complex, and 3) Intelligent. Intelligent failures are undesired results of thoughtful forays into novel territory.

Dr. Edmondson next shared three examples of failures. In the early days of Toyota’s plant in Georgetown, Kentucky, the plant was having a problem with seats. This is a preventable failure. To learn from failure in routine operations, leaders should identify problems and root causes, devise improvements, and re-invigorate improvement practices. Indeed, Toyota’s problems with floor mats several years ago resulted, ironically, from leaders’ failure to apply “the Toyota Way.”

At Children’s Hospital in Minnesota, a 10-year-old boy received an unsafe overdose of morphine. Eight little failures led to this massive mistake, which was a complex failure. To learn from failure in complex operations, leaders should make sure it’s safe to talk about errors. They should test systems and implement improvements and test them again.

An example of intelligent failure is Eli Lilly’s experimental chemotherapy drug, Alimta, which failed in clinical trials. Though this outcome was undesired, it was an intelligent failure. The best strategy for learning from intelligent failures it to push for more failures and identify lessons from the failures so that the same failures are not repeated.

The traditional mindset towards failure is that it is not acceptable – that is, effective performers don’t fail, and managers should prevent failure. We need to re-frame failure to see it as a natural by-product of experimentation. Effective performers show curiosity and learn from failure, and effective managers promote learning.

Rajesh Ranganathan from the National Institutes of Health asked Dr. Edmondson if she could describe what psychological safety looks like in senior teams. Dr. Edmondson responded that according to the literature, it’s desirable to have task conflict, but not personal or relationship conflict. In the real world, however, it’s very difficult to have task conflict without personal conflict, and the advice to stay away from personal feelings gets us nowhere. Psychological safety is critical in order to help senior teams challenge one another’s ideas while preserving their relationships.

James Cobb from Novartis pointed out that even in a psychologically safe organization, if success is rewarded so greatly, it’s difficult to embrace failure. Dr. Edmondson agreed that this is challenge.

Janni Wilson from Hilton Worldwide asked about strategic failure. If a system does not have the tools to process everything it needs to process, the team should sometimes decide to fail strategically. Dr. Edmondson said she would categorize strategic failure as intelligent failure, unless there were people in the organization who had information that would have prevented the failure and did not share it.

Gordon Batty from Gannett expressed that it is difficult to embrace failure in organizations. Dr. Edmondson says that part of how we can reframe failure is by talking about it in different ways. Unsuccessful failures are mission-critical. Marga Biller from LILA asked about first steps leaders could take to create a culture in which failure is embraced. Dr. Edmondson suggested starting by sharing stories of failures that led to personal and organizational learning.

Peter Fasolo from Johnson & Johnson brought up the dimension of time as a complicating factor in learning from failure. If there is not time for reflection, it’s difficult to learn from failure. As an employee, your willingness to take risks is correlated with sponsorship, that is to say, a leader saying that it is worth your time, that they have your back, and that they will support your efforts regardless of the outcome. Often, the cause of an error is not the person who makes the error; it is the lack of support the person is receiving from his or her supervisor. Dr. Edmondson connected this concept to the rescue of the Chilean miners, in which case the leadership support was tremendous.

Dr. Edmondson closed by presenting five leadership behaviors that promote learning:

- Frame the work accurately. Is this task routine, complex, or innovative? The framing depends on the type of task you face.

- Acknowledge limits, and that you know that you’re fallible.

- Embrace messengers.

- Listen intently.

- Encourage dissent. Alfred P. Sloan once said, “Gentlemen, I take it we are all in complete agreement on the decision…Then I propose we postpone further discussion of this matter until our next meeting to give ourselves time to develop disagreement and perhaps gain some understanding of what the decision is all about.”

Finally, Dr. Edmondson encouraged us to aim high, team up, fail well, learn fast, and repeat.

Add a comment