During the October gathering, LILA members identified several puzzles related to system leadership. These included:

- What is the role of curiosity in being able to scan the system?

- How do we encourage curiosity as a way of opening up the path for system change?

- How can we measure and reward curiosity?

- How do you foster national curiosity to learn, especially given the fact that things are changing so rapidly and that we have new technology and that impacts, not just what we learn, but how we learn?

View the presentation recording

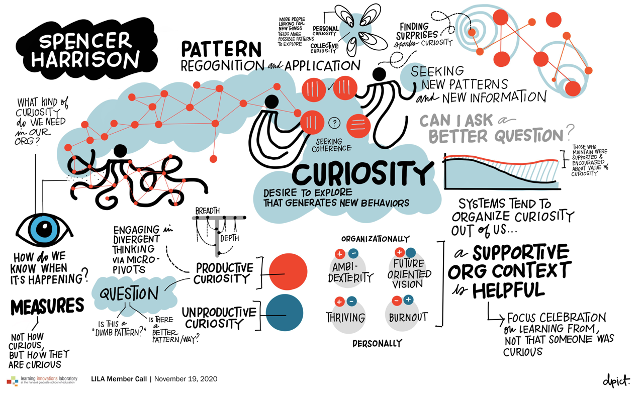

Given these puzzles, we invited Spencer Harrison to share his current research and thinking to inform our exploration. Spencer began by having us engage in an exercise – asking us to count from one to 60 in 60 seconds by finding all the numbers in this image:

This was not an easy task. Most LILA members were able to count up to the middle teens – one outlier got to 24 (go Ben). However, once Spencer added a grid, we were able to more easily pick up the pattern and achieve the goal of the exercise.

As human beings, we are really good at creating patterns and using those patterns over and over again allowing us to be efficient. Organizations do this as well. For example, if we have good market research, the organization is able to see the patterns that are out in the market about what consumers want and provide it through its products and services. The internal patterns match the external patterns and that allows the organization to grow and be effective. But eventually, the consumer’s patterns change. But eventually, their patterns change, what they expect from the organization, what they want from the products differ. At that point, if our patterns inside the organization don’t keep pace, then as an organization, we begin to decline. If we think about system leadership, how do we recognize patterns that are important and then when do we change those patterns, based on the new information. Curiosity plays a key role here. Our brains are really good at recognizing patterns, and also at finding new pieces of information.

In groups, pattern recognition overtakes the curiosity balancing that we would do on an individual basis. Once we are surrounded by other people, we stop asking ourselves is this the right pattern we are seeing and instead ask is this the pattern that everyone else is using? And if it is, then I should probably use that same pattern. That results in our patterns becoming “dumb” over time. The pattern isn’t matching anything that is useful, it’s just allowing us a sense of social acceptance and that becomes the danger zone for organizations. Patterns in this sense can be leadership behaviors, they can be cultural factors, organizational identity or market position. Curiosity becomes a linchpin that can allow organizations to adapt and adopt new patterns over time, it is part of their DNA.

Curiosity is a great source of new ideas, a great source of finding these patterns – and yet the majority of people don’t feel like they have permission to be curious at work. Spencer and his colleagues spent six months creating a new set of measures to assess curiosity. During this process, he and his colleagues identified that there are different types of curiosity. There is productive curiosity – where someone is actively investigating problems that are associated with the work that they’re doing. And unproductive curiosity, where someone is taking a break at work to look at something else – usually sports or social media related and doesn’t have anything to do with work. These two types have different consequences.

What the research surfaced was that the curiosity of senior leaders has a sustaining impact on the organization – it allowed the leaders to maximize their existing patterns and also allowed them to explore new patterns. The higher productive curiosity is among senior leaders, the more likely an organization is to embark on organizational ambidexterity where it is really good at using existing resources and at the same time to explore new ways of deploying those resources and innovating their strategies. So, it’s both a short-term focus and this long-term focus and balancing them.

When asked to create a 5-year vision for the organization, people that are more productively curious are less focused on the present and more focused on the future. This future orientation allows them to take a longer view of what’s going on in the organization. An added finding was that those individuals who have high productive curiosity also feel a sense of thriving in their job and consequently, that thriving leads to less of a sense of burnout. People actually enjoy what they are doing, the work makes them feel rejuvenating, it gives them a kind of physical energy and that allows them to go about the work that they are doing. This leads the organization itself to create an innovative climate. Not surprisingly, when people were unproductively curious, when they are taking breaks to explore other issues that are outside of their work, that curiosity actually has a negative impact on their ambidexterity, especially on the exploration side. Organizations that had leaders that were unproductive in their curiosity were less likely to embrace new innovative strategies and actually led to a lower sense of thriving and higher burnout of the individuals. While that might seem counterintuitive, unproductive curiosity is a signal to yourself that you really don’t like what it is you’re doing and so as a result, you feel like you are “dying” a little bit inside each time you have to return to work and that’s what leads to the burnout.

Spencer and his colleagues developed skills that measure whether or not the organizational climate leads to a sense of feeling encouraged to be curious or discouraged to be curious.

In organizational climates where curiosity is encouraged, individuals felt a stronger sense of thriving which strongly correlates with resilience as well. This in turn leads to a stronger sense of satisfaction with the organization.

Spencer ended the formal part of the presentation by suggesting that a technique for improving curiosity is to ask yourself “Can I ask a better question?” For example, if the initial question is “What would my biggest competitor do if they were in my position?” a better question could be to ask, “What would my biggest competitor do if they were my collaborator. Even if the original question has value, the additional questions allows us to seek new information and discover new sorts of patterns that can then orient our organizations to new ways in which they might want to change. This simple approach signals to the people around us that we’re open to having them ask questions and try on new things.

In summary, curiosity, can sustain our future because it allows us to recognize the patterns that we do have and then begin to explore for new information that might invalidate those patterns, requiring us to seek for new patterns as we think about how the systems in our organization might need to change and adapt for a future. We also went through some data to show that curiosity influences, not only you, but also the organization and the people around you. We can develop curiosity, just by interacting with people in slightly different ways, for example by using the “Can I ask a better question technique.”

Questions & Answers

What is curiosity and can it be reawakened if lost?

The broad definition that we use in psychology is that curiosity is typically defined curiosity as the desire to explore that leads to us finding new information. Hal Gregersen and colleagues (including Spencer) conducted research that question asking among children declines over time. A 5-year-old asks 200 to 300 questions per day and an 18-year-old in the United States on average, asks one question per month. The one question per month is it’s a little bit skewed because that’s the number of questions that students are asking in class and the questions that you’re asking when you’re five are massive exploratory questions. What we learn over time is that question asking, and curiosity isn’t what people want. It becomes a vertical power relationship – teachers ask questions because they know the answer and want us to figure it out. In a study of Nobel Prize winners, they found that their curiosity becomes preserved by a mentor and that sticks with them their entire lives. Our systems educate curiosity out of people.

How did you define productive versus unproductive curiosity knowing that innovation can happen when you look at unproductive or “irrelevant” things?

We started by getting 500 descriptions from individuals about moments when they had been curious and to sort of impact that that curiosity and had on work. Once we understood the impact we separated those into two groups productive and unproductive. Then we worked backwards to figure out what was going on in each one of those. What we found is that that productive curiosity doesn’t mean that I’m locked into the task that I’m doing. In fact, people are really good at doing what we were calling micro pivots where they are stepping out of a task stream and thinking more broadly about what’s going on. They were doing divergent things, but they didn’t completely step away from the task. Unproductive curiosity was when people described listening in on gossip because I’m curious about what’s going on. Or I’m checking a website or I’m on social media or I’m just trying to discover a little bit of information that that allow me to distract myself from the work that I’m doing. Whereas productive curiosity was s deliberate choice to try to understand a bigger world and see a bigger pattern and then returned back to the task with a new idea or a way to experiment within that pattern.

They’re both divergent. They’re just divergent in different ways and they give people access to different types of information.

What are some signs that curiosity is happening?

Organizations create a normative line around what curiosity is and what curiosity is not. They decide what amount of play and experimentation they will allow. Managers often pushback and say that they can’t afford to have employees not focus 100% of their time on execution. The real question is can they afford not to? Part of it is having an appetite for failure and making sure that the failure is based on a question or an exploration that brings back some data that informs whether to continue on that path again or to determine if we go down that path again, let’s explore it in a different way.

Is there a point at which you can have too much curiosity?

Its probably a curvilinear relationship where you can have too much curiosity and at that point, you’re spending the whole day being divergent and you’re not buckling down on things. IDEO has been thinking about the optimal combination of personality traits that you would want in an employee. They tried to hire people with“T” skills; people that are divergent in a lot of areas and also have deep expertise. The premise is that if you have the capability of going deep with your expertise, it probably means, at some level, you have persistence or high conscientiousness which allows you to be detailed focused and you also have curiosity that allows you to have some depth. If you think about Angela Duckworth’s notion of grit, what often sticks out to people is the idea of persistence. She was also measuring curiosity as part of it.

Is curiosity multicultural?

In the same way that the question asking we do can be shaped by the social forces that we encounter, those same things are going to help shape the way that we can be curious as well. Let me give you one example. We’ve already talked about how questions can be a way of kind of “behaving ourselves” into the motivation to be curious. Another thing that’s a powerful catalyst for curiosity is finding surprises. You can do that by telling yourself that today I’m going to look for five surprising things. What research shows is that when I have a sense that there is greater paradox available in the world, it actually makes it harder for me to be surprised because I tell myself – that’s what’s supposed to happen without having hypotheses about it. And if we’re not surprised, then it can be harder for us to be curious as well. All of these things are going to be shaped culturally in different ways. The challenge for us is to constantly be wrestling with our patterns and to make sure that we’re thinking about whether there are patterns that we’ve accepted that are “dumb patterns.” Am I just doing it because everybody else is around me or is there a better way of doing this? What if we adopted a different approach?

Is there a link between curiosity and resilience?

The research that I did which is included in Adam Grants book Plan B. This research is about how people overcome stress tragedy. I was examining the case of the plane crash in 1972 that the book Alive is based on about the airplane crash in the Andes. How would they survive? What we found was that the individuals that are able to maintain curiosity over time were constantly acquiring new hypotheses about the way the world works. Those hypotheses don’t disrupt the group because the group latches onto initial hope about how they’re going to be able to survive the horrible circumstance. When new information emerges that turns that hope into despair. However, the people that have been curious and have been exploring new ways of thinking were able to immediately jump in and offer a new hope that then resurrects the resiliency of the group and allows them to push on. That experience, the transition between the people that are hopeful and people that are curious happens at least four times. Each time there’s a transition, new materials emerge from the group that ultimately as a collection, allow them to thrive and to solve the situation they were in. what that example shows is that you need this constant influx of fresh ideas because none of us fully comprehend the complexities of the environments that we’re working in all of them are changing.

What the example shows is that you need this constant influx of fresh ideas because none of us fully comprehend the complexities of the environments that we’re working in and all of them are changing constantly. In fact, for most of us, the pattern you have today is going to be out of date at some point, but that happens slowly over time. So ,what you need is something that allows you to constantly update the pattern.

Do we know the causal direction when you’re talking about curiosity – is it leading to thriving at work or if you’re thriving at work, you’re more curious?

For a long time, there’s been what’s called the broaden and build hypothesis. The idea is that when I feel positive emotion which is typically strongly correlated with being curious, then that opens up my mental pathways to explore for new information. Then when I discover new information, I actually feel positive about that. That then opens the pathways even more. So, there’s this reciprocal loop. In a study we measured curiosity first and then we measured thriving later. We are actually going to measure it again in a few months to see how long the relationship holds. In earlier studies that I conducted, we looked at daily moments of curiosity that showed a similar model. For example, if you were curious in the morning did that have a more positive effect in the afternoon or, if you were curious on Monday, did you have a better day as well. There is a carryover effect, both within a day and from day to day.

How might we select for curiosity?

Our curiosity can be conditioned by national culture. It can also be conditioned by organizational culture. Coming up with the best way to select for curiosity has to take these two factors into account. You can use scenarios and behavioral event interviews. But perhaps one of the best is to ask them to describe something that they’ve learned in the last month and how you went about trying to discover it. If it’s that they picked up a book, it doesn’t show much more a willingness to read something versus if they said, found this book and I thought that was really interesting and then I talked to a friend who pointed me to this video, etc. They are then showing a willingness to not just take things at face value, but to dig a couple levels deeper. We are looking at measures of curiosity, but they also capture a lot of extraneous information. So, what we are trying to do is get things that were specific to a work context that have good measurement properties. We are trying to see what the patterns of curiosity are over time.

I’m wondering about the value of the hero who comes in with the answer to fix everything. How can we flip it, so the hero is the one unlocking the curiosity to get the increased performance? And how do we make the business case for that?

We have a ton of research that shows that curiosity leads to greater creativity and getting better feedback, but when you think about it at an organizational level we haven’t made that connection yet. At the systems level, we really struggle with the narrative that we have around collectives versus individual. It’s not about a hero coming in and fixing everything, it’s about the collective’s ability to draw resource from themselves. In terms of organizational culture, are we encouraging or discouraging curiosity? We all recognize that you’re coming to LILA because you can ask questions here that you can’t ask in other places.

How can I foster curiosity about a new initiative instead of immediate resistance?

We often think about change as being driven from outside urgency and therefore we need to adopt this system that someone else has already figured out and we need to get all our leaders to do it. That’s based on negative emotions and a sense of “we have to do it or else”. Negative exigency doesn’t force people to change – people change because they’re energized and excited about the future and they’ve been able to be curious and experiment.

Add a comment