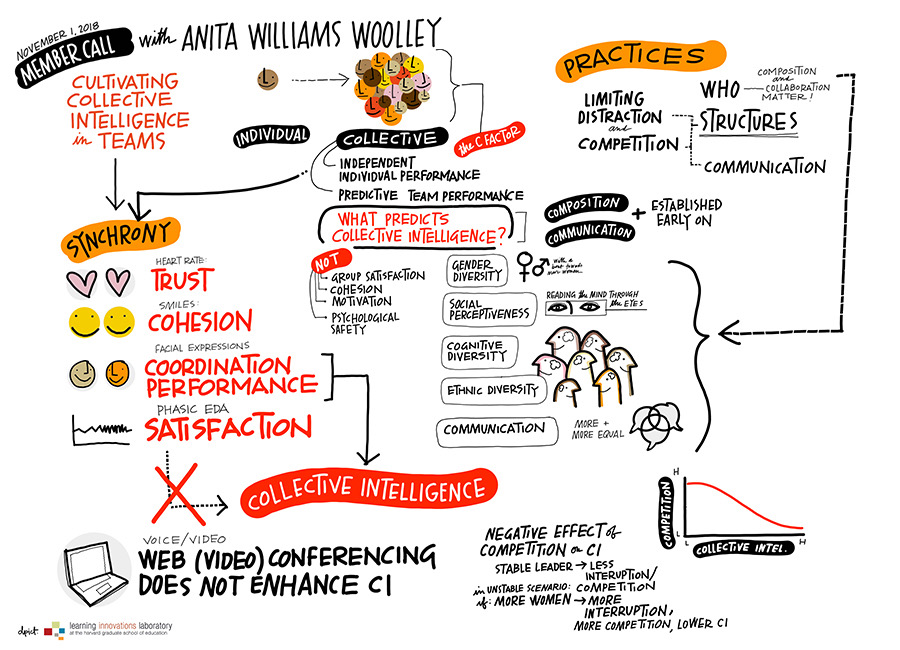

Until recently, organizations thought that if they wanted to create “smart” teams, they just had to hire smart individuals and put them together. But researchers have discovered that is not the case. Other explanatory factors account for the performance of teams more than simply the combined intelligence of individual team members. Anita Woolley has specifically focused on examining if there is an underlying collective intelligence (CI) that lets some teams perform better than others and, if so, can we measure it, use it to predict team future performance, and reliably create it?

What leads to “smart” groups?

There were many factors that did not correlate with CI, including interpersonal relationship quality (how members feel about each other), group satisfaction, cohesion, motivation, and psychological safety.

There were some factors that did seem to have a relationship with CI:

• Number of women on the team: Woolley’s studies found a curvilinear relationship between gender and CI. Teams oscillate around average CI until they begin to be majority female, at which point they are above average CI. All-female teams’ CI then go back down towards average again. These results about gender seem to be related to the other factors they found (see below) that correlated to CI as well.

• Social perceptiveness: They used the Reading the Mind in the Eyes test to measure social perceptiveness. This test shows participants pictures of people’s eyes and asks them to identify what the person is thinking or feeling, and it tends to predict how people will operate in social situations. Teams that scored higher on these tests tended to have higher CI, and more women tended to score higher on these tests.

• Cognitive style diversity: They also looked at three different cognitive styles (engineering and mathematics, visual arts and design, and verbally oriented styles). Teams need to be at least moderately diverse in cognitive styles in order to reach the highest levels of CI.

• Ethnic diversity: This showed similar patterns to cognitive styles: teams needed to have at least a moderate level of diversity to reach higher levels of CI.

• Amount and quality of communication: Their studies showed that more communication and more equal communication between group members related to more CI. These results showed up both in in-person groups and in groups working together online over chat or email. In general women tended to be higher in social perceptiveness and therefore made for more equal communication in groups by noticing how much they and other people are talking and playing a facilitator role of calling on people who haven’t spoken as much.

How might CI relate to Collective Mindfulness?

While Woolley hasn’t looked at the relationship between CI and mindfulness specifically, she expects that there would be a correlation. Revisiting our working definition of collective mindfulness and discussions during the October LILA gathering, we find some clues.

For example, the right conditions for CI are associated with outcomes such as more communication and more equal communication among members. Increased and more equal communication among members set the stage for groups to surface new information and divergent perspectives that help them make decisions more intentionally or to re-examine their default assumptions and processes – in line with our working definition of collective mindfulness.

Collective mindfulness is the ability of a system to communicate, interact, and operate in ways that avoid functioning on autopilot; that instead are imbued with shared and emergent awareness, observation, and intention.

Learning Innovations Laboratory Confidential Nov 1, 2018 Page

5

Some organizing practices that may facilitate both CI and collective mindfulness include some that were discussed by Cristina Flesher Fominaya from the Oct LILA gathering:

INSTALL A FACILITATOR – whether a role filled by an external person or a role that rotates among team members. A facilitator that likely creates conditions for CI and collective mindfulness:

▪ Makes sure all people feel able to participate and feel listened to

▪ Keep people on track when people get off the point

▪ Make sure not just one voice dominates the conversation

BUILD UP RELATIONAL BONDS. Social perceptiveness and facial and audio synchrony appear to be important in CI and are likely elements toward building relational bonds that can help members of a group and organization be more willing to listen to and work with one another toward collective mindfulness (which can be uncomfortable – see David Perkin’s 10,000-foot view from October Gathering).

In turn, greater relational bonding may also increase the likelihood of social perceptiveness and facial and audio synchrony because we better understand our teammates and their feelings and interpretation of events. It becomes what can be called a virtuous cycle (note, however, that we are not yet aware of research that has shown all these connections).

One way of starting the cycle could be practices that build up relational bonding:

▪ Do a check in. When you come in the morning, before you talk about any of the goals you’re doing, you check in about how everyone is doing. This gets people feeling that others care about them.

▪ Do a daily check-up (which can follow a daily stand up). It involves: here’s what I did yesterday, and here’s what I’m doing today. It gives everyone an awareness of what everyone else is working on. It also serves also for accountability and also serves agility because you get a sense of what everyone else is working on.

▪ Retreats where all business is set aside, and you just bond relationally.

Add a comment